| Keneth Sparr |

The Early Period

The lute was known in Sweden as early as in the beginning of the 15th century and we find many traces of it during the following centuries. The same cannot be said about the guitar. It was a fairly unknown instrument until the 19th century even if there are some scattered references to it during the preceding centuries. A painting in the Edebo church in Uppland that can be dated 1514 might even suggest the appearance of the vihuela da mano in Sweden already in the early 16th century.

The vihuela player from Edebo Church, Uppland, Sweden.

However, iconographical evidence is always dubious when not supported by other facts and nothing has so far been discovered that might confirm the use of a vihuela in Sweden. Most likely the artist in this case has taken his model from abroad, but the painting is still interesting as a very early representation of the vihuela. On the top of the Edebo instrument we find the inlays characteristic of the vihuela. There are some odd things about the instrument: the lack of a central soundhole, the bent-back pegbox and the fact that the strings are attached to the lower end of the body. The bent-back pegbox, however, is not unique to our instrument. You may find the same in the famous engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi of a man playing a five-course vihuela or viola da mano. As a matter of fact this engraving is contemporary with the one in the Edebo church.

The 17th and 18th Centuries

We have to go to the 17th century to find more substantial evidence of the guitar’s presence in Sweden and from this period we have both documents and preserved music. From an inventory of the property of the Governor General Gustaf Adam Banér (1631-1681) we learn that he had owned two printed guitar tablature books: Antonio Carbonchi’s “Sonate di Chitarra spagnola” (1640) and “Le dodici chitarre spostate” (1643). These may have been acquired during Banér’s peregrination and he visited Italy in 1650. In the inventory are also mentioned “Diversae Tabulaturer, Vthi ett stoort Volumen” [Divers tablatures, in a big volume], but it is not certain whether these contained music for the guitar, lute or a keyboard instrument. From 1669 there is scant information about Carl Gustaf Wrangel’s daughter Maria Juliana, owner of Skokloster castle, and married to Nils Brahe in 1660 Maria Juliana inherited a guitar from her sister Polidora Christina in 1669. During the period 1652-1654 Queen Christine of Sweden had a company of Italian musicians and actors employed. Among these musicians you find the theorbist and guitarist Angiol Michele Bartolotti as well as the singer, lutenist and guitarist Pietro Francesco Reggio. Bartolotti furthermore dedicated his “Secondo Libro di Chitarra…” to “alla real’ maesta della Regina di Svetia”. During her exile in Rome Queen Christina certainly came in contact with guitar players. It is most certain that the Spanish guitarist Gaspar Sanz dedicated his Dos trompetas de la reyna de Suecia to Queen Christina. The short piece is found in one of the most famous collections of guitar music, “Instruccion de musica sobre la guitarra española”. It suggests that she and Sanz might have met, since we know that Sanz studied music in Rome in the middle of the 17th Century as a pupil of Lelio Colista. They may have met at the Accademia degli Stravaganti which at the time was under Christina’s patronage. Johan Ekeblad, courtier at Queen Christina’s court, in a letter dated Stockholm 1662 wrote that he would like to have his guitar brought to him, but the case was too damaged. At the Swedish court during the reign of the Queen Dowager Hedvig Eleonora a guitar teacher by the name of Jean l’anis was employed between November 1671 and March 1673. He taught the princesses Magdalena Sibylla and Juliana on the guitar and his pupils were each given a “Chitarbook”, valued at eight silver daler. In December 1671 Gustaf Düben, the leader of the “Hofkapelle”, was paid for a repair on a “Quitarre”. The Queen Hedvig Eleonora also owned a tablature book, which may be identical with one preserved in the Diocesan and Regional Library in Skara (Katedralskolans musiksamling 493b, nr 31). This manuscript was to a great extent written by Gustaf Düben in 1659 and in it a few pieces in tablature for the guitar were noted at a later time, possibly by Jean l’anis.

An important collection of music for the five-course guitar, both in print and in manuscript, is kept in the Norrköping City Library, the so called Finspång collection. In this collection you may find the unique copy of Rémy Médard’s “Pièces de guitarre” (1676) as well as two manuscripts (Finspong 9096:2 and 9096:14) with a strong connection to Médard.

Louis de Geer (1655-1691). Either of these may have acquired the manuscripts and the printed book in Paris and may even have been taught the guitar by Médard himself in the 1680s.

Another interesting manuscript which contains eight pages with tablature for the guitar is kept in the Diocesan and Regional Library in Skara (Katedralskolans musiksamling 468). On the first folio you find the following written: “Hedevig Mörner Commence a jouer sur la Gittare chez Mons: Bocthage dans le mois de Novembre l’an 1692, sur la recommendation de son fidel serviteur Ekeblad”. This gives us a clear provenance and dating of the manuscript, but unfortunately I have not yet been able to identify the guitar teacher Bocthage, who might also have written the pages with music for the guitar. Hedvig Mörner (1672-1753) was an attendant at the court and married Clas Ekeblad, son to the above mentioned Johan Ekeblad, in April 1692. The manuscript contains primarily pieces with a French origin. Finally, in the archive from the castle of Eriksberg, now housed in the Swedish National Archive, yet another guitar tablature is kept (Eriksbergsarkivet, Manuskript- och avskriftsamlingen 52 C). It probably dates from the last decade of the 17th century and seems to be of Swedish origin although many titles are written in French. The notation lacks in most cases bars and the manuscript has the appearance of being written by an amateur. In the inventory, dated 1692, after the singer in the royal “Hofkapelle”, Nicolaus Olai Hiller, we find among other instruments a “Chitar” valued at eight copper daler.

From the 18th century we have very little information on the use of the guitar in Sweden. From some inventories however we may gather at least some facts.

A thorough research has been done by Berit Ozolins of the inventories from Gothenburg during the period 1690-1854. In the following I will cite her notes concerning plucked string instruments. From the 18th century the following notes are to be found:

– 1714 Johan Brun received a “chitar” and a “cetrin?”

– 1714 the architect Hans Palm “1 Chitar – 1 flöjt 6,,” (1 guitar, 1 flute)

– 1716 the former barber-surgeon at the admiralty Joh. Hindrich Kaldiners “1 citrinquen 3,,” (1 citrinchen)

– 1731 the merchant Carl Söderberg “en citrinque” (1 citrinchen)

– 1752 the merchant Peter Ekman and his wife Johanna “1 zitrin iken 2,,” (1 citrinchen)

– 1784 the wife of the corporal Joh. Hindr. Heins “1 zitra 12.- 1 d:o ofärdig 10.-” (1 cister, 1 ditto unfinished)

– 1789 the merchant James Marshall “Lagret: 23 st gitare” (in stock: 23 guitars)

– 1789 the merchant Joh. Gerh. von Ölcken “1 cittra -.32” (1 cister)

– 1793 the merchant Hans Törnvall “1 gammal zitra-.6 .-” (1 old cister)

– 1798 the principal Olof Wenngren “1 cittra utan strängar” (1 cister without strings)

The dominance of cisterinstrument is obvious and there also was a great import to Gothenburg of cisterstrings. Just to give an example: in 1651-1652 not less than 14 dozens of cisterstrings were imported. Another guitar “without strings” together with a bandora and two citrinchen is noted in the inventory 1732 after the court trumpeter Christian Zeising, and yet another guitar is mentioned in an inventory dated 1789. Among the few preserved guitars in Sweden from earlier times we can find one made by Joachim Tielke in Hamburg 1704. This guitar was in a private collection at the Wallox-Säby estate in Uppland, but its whereabout now is unknown. This guitar had undergone changes in the 19th century and was changed to six single strings with a new bridge etc. Another guitar from the 18th century is one made in 1792 by Josef Benedid in Cadiz, now also in a private collection. However it is more likely that this particular guitar was brought to Sweden in the early 19th century. The only guitar known to have been made in Sweden until the 19th century was made by Sven (Sueno) Beckman in Stockholm 1757 and its corpus consisted of tortoise shell and it had a sculptured head according to the description when it was sold at the Christian Hammer auction in Cologne in 1892. It should once have belonged to Queen Lovisa Ulrika of Sweden. It may be identical with the guitar (or sooner guitar-cittern hybrid) by Sven Beckman dated 1757 which is kept in the Royal College of Music, Museum of Instruments, London. The outline of the body shape is certainly that of a guitar. The descriptions do not quite match. The Beckman in RCM (with catalogue number RCM 23) has a sculptured head but back and sides are of maple and it is the fingerboard which is veneered in tortoiseshell. One of the very rare instances when a guitar is mentioned in connection with a concert is when Giordani, Inverardi and Folchini performed in Stockholm on July 19th 1798. At this occassion a divertissement for viola englese, lute and guitar was played. In the library of the Music Museum in Stockholm we also may find a copy of Giachomo Merchi’s Le Guide des Ecoliers…, but the Swedish use of this method is uncertain. It probably is a part of the Daniel Fryklund collection (see below!).

During particularly the 18th and the beginning 19th centuries there was a considerable confusion in the terminology of the guitar, lute and cister. The Swedish word “Cittra” [cister] in many instances was used for the guitar or the lute. Often it is impossible to tell which of these instruments is meant. Another complication is that during the last decades of the 18th century the so called Swedish lute appeared on the stage. This unique type of instrument originated probably from the cister, but it had roughly the shape of the lute, single strings (gut and overspun) and a different tuning. The Swedish lute (often also called “Cittra”) flourished c. 1790-1820 and the music for it was written in staff notation on one system, quite similar to to guitar notation. The Swedish lute was much appreciated and its widespread use may have delayed the reintroduction of the guitar in Sweden at least a decade. Another reason for this delay may have been the prohibition of import of musical instruments into Sweden which lasted from 1756 until 1816. For more information on the Swedish lute see my article “The improved cittern”. Catalogue of Manuscript and Printed Music for the Swedish Lute.

The First Decades of the 19th Century

Even if the Swedish lute still dominated during the beginning decades of the 19th century the guitar slowly tried to make its way. The most renowned maker of Swedish lutes, Matthias Peter Kraft, made a guitar in 1800. In the newspaper Dagligt Allehanda No. 216, 22 September 1801 Trille Labarre’s “Nouvelle méthode pour la guitare” (a copy of which is in the author’s collection) was advertised for sale by the Librairie Française i Stockholm and a couple of years later, in 1804, the German edition of Charles Doisy’s “Principes généraux de la guitare” was introduced. We also have a few early guitar methods preserved in our libraries as those by Henry, Phillis and Ferandiere. As I stated above we cannot be certain that they were used in Sweden at this time. In 1812 the Duke of Pienne, visiting the Löfstad castle, made a painting in water-colours showing himself together with Carl Fredrik and Sophie Piper (1757-1816). Carl Fredrik Piper is playing a guitar on the painting and we may guess that the Duke had brought this from France. The Duchess Charlotte (later queen of Sweden) describes Sophie Piper in the following manner in her diary:

Hon har vissa talanger och sjunger ganska nätt och knäpper bra på gitarr, men uteslutande i en mindre krets av vänner [She has certain talents, sings rather nicely and plucks the guitar well, but only in a small company with friends].

In the memoirs of Malla Montgomery-Silfverstolpe concerning the period 1815-1816 the following is related:

Count Gösta Lewenhaupt was at Kaflås, sung niecely and played the guitar. His Spanish and Italian songs pleased Malla. She lived in a room beside the drawing-room and often woke up and fell asleep to his music.

There are also a few, scattered advertisements offering primarily guitar schools and exercises to be found up to 1815 when the Musikaliska Magazinet in their catalogue of newly arrived music also listed music for the guitar by “Carulli, Molino, Gänsbacher, Harder, Bortolazzi, Kargl”. Lorents Mollenberg, who had been trained by and worked with Matthias Peter Kraft, made a few guitars, of which the earliest known is dated 1816. Another guitarmaker who flourished at least in 1817 and of which practically nothing is known was Henric Gottlieb Becker. He probably is identical with G. Becker from Stralsund, by whom a guitar dated 1814 is preserved in the Collection Fryklund at the Music Museum in Stockholm. There is information about Carl Eric Sundberg (1771?-1846) in Stockholm, who made “Harpor, Sittror och Gitarrer (harps, cisters and guitars)”, but also keyboard instruments. He finished as a musical instrument maker in 1833.Guitars were also made in the provinces and one example is the guitar-maker J. Andersson in Skara, by whom two guitars are preserved. We have also information about the keyboard maker Johan Heinrich Daug (1786-1844) in Gothenburg that he both made repaired and guitars as well as manufactured strings for the guitar. Another musical instrument maker in Gothenburg was Carl Ljungberg (1783-1835). In his estate inventory two half-finishedd guitars are mentioned. The keyboard maker Johannes Jonsson (1784-1857) in Gothenburg also made guitars according a note from 1831.About Lazarus Heyman Salomon/Salomonson (1817-1898), also in Gothenburg was saidin 1837 that he since 1 March 1832 had made several guitars. But most guitars were certainly imported. In my own collection you may find an anonymous six-course Spanish or Portuguese guitar as well as an anoymous French guitar from the first decades of the 19th century

The first printed Swedish music for the guitar was published in 1818 by Friedrich Ludwig Fehr and Johan Carl Müller, two foreign lithographers who had established themselves in Stockholm. This publication was entitled “Verschiedene Tänze und ein Marsch für die Guitarre…” and the music was composed by Fredrik Wilhelm Hildebrand (1785-1830). Hildebrand was German by origin and had been a pupil of Louis Spohr. Before Hildebrand went to Sweden he had by C. F. Peters published a few collections for song and guitar and a “Fantaisie” for solo guitar. He became violin-player at the Swedish “Hofkapelle” in 1816 and took active part in musical life in Stockholm during the 1820s. He published several works for the guitar including a collection of Swedish folksongs, a “Fantaisie lugubre…”, “Six Polonaises pour Violon ou Flûte avec accompagnement de Pianoforte ou Guitarre…” and a pseudo-periodical “Journal för Guitarre”. Some fo these were advertised in newspapers in Uppsala. He also arranged the guitar accompaniment to several collections of music by Bernhard Crusell with texts by Esaias Tegnér, the most prominent Swedish poet at that time.

From 1818 and onwards there was a considerable increase in the import of and advertising about guitar music, tutors, guitars and Roman strings. The 1820 catalogue of Östergrén’s musicshop contained 43 items for the guitar and this kind of material became common in the catalogues of publishers, musicshops and music loan and rental libraries. However the guitar was not a very common instrument in the 1820s as can be seen from a contemporary description by the Swedish composer Otto Lindblad:

One evening in the winter I passed a house from where music and singing could be heard. In the house lived a musical director Liebert Schmidt, who on this occasion had a gathering. I stopped and listened to the sounds until I was almost frozen to ice. I got the opportunity to see the instrument upon which he played – it was a guitar, a rare instrument at this time…

Lindblad then tells how he tried to make his own guitar with little success, but evidently the instrument had made a certain impression on him. In 1825 a J. Nystedt in Uppsala offers tuition in “violin, guitar and fortepiano and accompaniment to fortepiano as well as tuning”. Nystedt repeats this advertisement in 1829. In 1828 a guitar is advertised for sale in a newspaper. The next year, 1829, a person (probably a student) advertises that he/she wants to rent a guitar the rest of the semester.

The plucked instruments including the guitar are more common in the inventories (from Gothenburg at least as shown by Berit Ozolins in her dissertation) from 1818 and onwards. Here are a list of guitars in inventories with their values in Riksdaler (Rixdollar):

– 1800 the widow of sergeant And. Hallberg “1 cittra utan strängar 2.-” (1 cister without strings)

– 1800 the town carpenter Fredr. Aug. Rex “1 cittra -.16” (1 cister)

– 1809 the wholesale merchant Bernh. Wohlfahrt “1 zittra 12.-” (1 cister)

– 1818 the wife of the language master Pierre de Flinne ” 1 gitarr med låda 10.-” (1 guitar with case)

– 1822 the bookeeper Laurentius Tiljander “1 guitarre 40.-” (1 guitar)

– 1824 the wholesale merchant Edv. Ludendorff ” 1 guitarre 10.-” (1 guitar)

– 1826 the wife of the (musical?) instrumentmaker Johan Henrik Daug “2 st guitarrer” (2 guitars)

– 1827 the winemerchant and lieutenant Johan Stuff ” 1 söndrig guitarre 1.16″ (1 broken guitar)

– 1828 the student Magnus Runnerström “1 guitarre med strängar 4.-” (1 guitar with strings)

– 1829 the wholesale merchant Per Backman “1 större luta med fouteral 10.-, 1 mindre luta med fouteral, 1 guitarre (pantsatt) 50.-” (1 big lute with case, 1 one smaller lute with case and 1 guitar pledged)

– 1829 the wife of the wholesale merchant A. Fröding “1 guitarre 7.-” (1 guitar)

– 1829 mrs Cecilia Charl. Hellstenius “1 gitarre 2.16” (1 guitar)

– 1829 the tinsmith Joh. Martin Nabstedt “1 gitarre” (1 guitar)

Hildebrand was not the only active guitarist in Sweden. Another one was Jöns Boman (1798-1849) who primarily published guitar accompaniments to songs, the first one being a collection from Carl Michael Bellman’s “Fredmans Epistlar”, printed in 1826. A collection of eight duets for two guitars by Boman was printed in 1835. The guitar “virtuoso” Charles de Gaertner (Carl von Gaertner) played at a concert in Gothenburg on August 15th 1820. He performed Giuliani’s grand concerto, a duett for guitar and violin by Carnesi and a “Fantasie sentimental, composed… by v. Gaertner, sometimes performed without using the right hand”. This particular skill he also announced the same year: “he performed a solo piece, sometimes without the use of the right hand, and a ‘concertino’, in which he blowed with his mouth without an instrument but with accompaniment on the guitar”! Gaertner also performed in Uppsala the same year (1820) and Samuel Ödmann reported in a letter:

We now have the virtuoso Gertner here. Yesterday afternoon he made me the pleasure of playing his guitar (Citthra) at my place. I was quite surprised of all the things that could be done on such an unimportant instrument, which usually is not worth listening to. I was particularly amused to hear the famous Fandango, about which I have read much, and the superbe song of the gondoliers in Venice…

Gaertner furthermore worked as a guitar teacher, which can been seen from his only known printed music, which can be dated 1819-1823: “Six Laendlers Pour la Guitare composées et Dediés A Mademoiselle Dorothee de Engeström par son maître…”. Gaertner is probably identical with Karl von Gärtner who for the first performed on the guitar in Vienna on March 19th 1824.

On April 23d 1822 the Italian guitarists and violinists Joachim and Pietro (Pierre) Pettoletti gave a concert in Gothenburg in which they performed a duo concertante for violins by Kreutzer, variations for two guitars with orchestral accompaniment by Giuliani and and a trio for three guitars by Bernhard Crusell. In 1829, or perhaps earlier, Pietro Pettoletti moved to Stockholm, possibly from Copenhagen where he together with Joachim had performed music by Giuliani and Carulli in a concert in 1826. Pettoletti published four collections of music for solo guitar during his stay in Stockholm. The first one was advertised as follows:

From the lithographic printer has appeared and is to be sold at the author’s home and at the music shops of Östergrén and Hedbom: Mes Souvenirs… by P. Pettoletti, who gives lesson in guitar-playing and lives in Stockholm at Norra Smedjegatan, house Nr 2, the block of S:t Peter.

“Mes Souvenirs…” was Pettoletti’s opus number six and only a couple of days later his seventh opus, “Variations pour la Guitarre… dediées à Monsieur le Baron Uno de Troil, Son Elève” left the presses. In September the same year another work appeared: “Six Variations faciles & agréables… Oeuvre 8”. The title of his opus 9 informs us that he had given a concert in Stockholm: “Pot-pourri pour la Guitarre… composé & exécuté à son concert à Stockholm en 1829”. On 19 March 1829 Pietro Pettoletti gave a concert Uppsala and he returned to this city on 18 October the same year for another performance. In 1830 Joachim and Pietro Pettoletti gave another three concerts in Gothenburg. The first occured on February 2d and included a variation for two guitars by Joachim Pettoletti, a quartet for voice, piano, guitar and violin by Moscheles, Giuliani and Mayseder, variations for guitar, violin, viola and cello by Paganini and divertissement for two guitars by Giuliani. The concert was reviewed in the newspaper Götheborgs Posten a couple of days later: “The concert given by the Pettoletti brothers was met with general approbation and was exceptionally well attended”. The next concert, “subscribed”, was given on March 11th. It included an ouverture by Joachim Pettoletti, a violin concerto by Libon performed by Joachim, variations for the guitar over themes by Carl Michael Bellman, performed and played by Pietro Pettoletti, a trio for violin, guitar and cello by Giuliani and a potpourri for two guitars. The last subscribed concert was given on March 23d. The brothers Pettoletti then performed a divertissement for two guitars, a “Variation sur la Tyrolienne” (the same work as the printed Variations… above), composed and played by “Mrs” Pettoletti, “Var. concertents pour violin et guitarre par Quiliani [sic]” and finally, a quartet for piano, violin, guitar and voice. How long Pietro and Joachim Pettoletti stayed in Sweden we don’t know, but Pietro later moved to Russia where he published many works. He died in S:t Petersburg in 1870.

Another foreign guitarist visiting Gothenburg was “doctor” Karl Töpfer (b. 1791), a German who earlier had performed in Vienna. He had also published several collections of music for the guitar. On September 16th 1827 he gave a concert which on the programme had the following works: some andantes, a rondo and German national anthems of his own composition as well as a theme with variations on Nel cor piu non mi sento, with accompaniment by another guitar, of which the last variations were “performed with the left hand only”. In the 1820s Otto Torp published “Six Laendlers Pour la Guitarre composés et dediés à Madamme Betty Waern Par son Maître”. This is his only known music published in Sweden. He must have left Sweden in the 1820s and established himself in the USA before 1828. He is recorded in the New York Evening Post on May 23rd 1828 as being a “Teacher of Spanish guitar and singing. Lately arrived from Europe”. In his new country he became a rather diligent editor and composer of guitar accompaniments to songs as well as methods for the guitar. About 1829 he published his “Instruction Book for the Spanish Guitar…” in New York and c. 1834 came his “New and Improved Method for the Spanish Guitar…”. Hewitt, Riley, Klemm and Firth & Hall published several songs with guitar accompaniment by Torp in the 1830s and 1840s and he is listed in New York city at various adresses:

25 Murray 1831

87 Greene 1832-1833 (as professor of music)

465 Broadway 1834 (as professor of music)

465 Broadway 1835-1836 (music store)

465 Broadway 1837 (musician)

229 Broadway 1838 (musician)

229 Broadway, h.8 Commerce 1839 (musician)

435 Broadway, h. 378 Houston 1840 (musician)

h. 378 Houston 1841 (musician)

It seems likely that he is identical with “Otto Torp, N.Y., wife and three children” who all were lost at the fire in August 1841 on the steamboat Erie at the lake Erie (many thanks to Joseph A Romeo who supplied me with this information). His death date can therefore be established as 1841. Torp may possibly be identical with the German (?) bassoon player Otto Torp, who is mentioned as Imperial Russian Chamber Musician, and who appeared at concerts in Gothenburg on 23 January 1825, in Uppsala on 27 November 1825 and in Jönköping in 1827. The blind Polish tenor singer and guitarist Wilhelm Bürow appeared in concerts in Stockholm, Gothenburg and Uppsala during the period 1825-1826, where he among other things sang arias from Tancred “accompanying himself on a nine-string guitar, invented by himself” and also performing a theme by Carafa with variations by Winter, with guitar accompaniment. The Milanes Antonio Ferrario together with a son traveled in Sweden in 1825-1826 performing both privately and in public, with mandoline, guitar and psaltery. They had earlier performed in St. Petersburg.

Frans Fredrik Edvard Brendler (1800-1831) only published one collection of songs to the text of Erik Johan Stagnelius in 1827. This was also the case with Edward Wilhelm Brandes (1804-?) who in his only collection 1829 used texts by Esaias Tegnér to his guitar accompaniments. Brandes appeared in a concert in Uppsala 11 September 1842 where he played “fantasys on a Double-Guitar, after a new method of tuning”, invented by himself. Another concert with Brandes was arranged on 3 October the same year and in this he performed the “ouverture to La dame blanc by Boieldieu, arranged for Double-Guitar with 12 strings” and a “Potpourri” for the same instrument. A C.A. Schulze published a “Rondo pour la Flute avec Guitarre” in 1825 which was advertised in Stockholm the same year and in Uppsala the following year. In 1829 the first printed guitar method in Swedish appeared. It was J. Müller‘s “Guitarre-skola eller Anvisning att stämma och Spela Guitarre efter Bornhardts, Carullis, Guileanis [sic], Hapders [sic] et Molinos Methoder”. This method was a short compilation but with a nice lithographic picture of a guitar patterned after earlier Austrian methods. Anton Gustaf Dannström (? – 1839) in 1832 published another method, “Guitarre-Skola efter Molinos, Carullis och Guillanis [sic] methoder…”. as well as “Polymnia” (1835), a collection of songs to accompaniment of the guitar and a collection of his own songs. In my own collection another early Swedish guitar method in manuscript is to be found. It may have been written between 1810 and 1835 by Johan Åbjörnsson (1794-1835). In 1833 two Swedish versions of Carulli’s method were published, one by A.W. Möller and the other by J.C. Hedbom. Both these versions were very successful and went through four or five editions until 1863. None of these followed Carulli’s original method in every detail and you may even find music by Carcassi in one of them. The one published by Hedbom was edited by Carl Friedrich Bock (1800-1841), born in Berlin but from 1829 flute- and clarinet-player at the Swedish “Hofkapelle”. He also arranged and published Johann Strauss’ “Rosa-Walzer” for the flute and the guitar. The Swedish guitar players had to wait until the beginning of the 1840s for a Swedish edition of Giuliani’s “Studio per la chitarra” and this was reprinted in a second edition in the late 1840s. The first original Swedish guitar method was written by a Carl Johan Grafström (1820-1892) and published in 1857.

In the late 1820s and the beginning 1830s there were many advertisements in the newspapers about guitars and strings for sale. The Swedish production of guitars was very small and strings were mostly imported. In 1834 J. C. Hedbom’s music shop announces that they have got guitars, “made after the model of Luigi Legnani”, from the factory of J. G. Stauffer in Vienna. Guitars were otherwise mainly imported from Germany (Dresden is particularly mentioned), Italy, Denmark, and Poland. In 1832 guitars with a tuning mechanism were advertised as an alternative to the usual wooden tuning pegs. France and particularly Italy were the main suppliers of strings. The most important supplier of strings seems to have been Ruffini in Rome.

1830-1850

It is not until the 1830s we can discern a real increase in domestic publishing of music for the guitar. There was not a great demand for solo music and c. 90 % of the published editions as well as the preserved manuscripts are intended for singing to guitar accompaniment. Several collections with names characteristic of the time as “Orphæa”, “Melpomene”, “Brage”, “Euphrosyne”, “Amanda”, “Aurore”, “Philomèle”, “Penelope”, “Urania” and “Adina” were published during the 1830s and 1840s. In 1832-1833 a musical periodical, “Necken”, edited by Jöns Boman and dedicated to the guitar was issued. It was to be followed by “Lördags-Magasin för Guitarrspelare” in 1839, “Bibliothek för Guitarr-spelare” in 1840 and “Nytt lördags-magasin för Guitarr-Spelare” in 1842. These periodicals were all rather short-lived. As well as in other parts of Europe arrangements from popular operas were in great demand. They were often published in close connection with the first appearance of the opera in Stockholm. Claes Lundin gives the following description from a boat trip near Stockholm in the early nineteenth century:

During the trip it was always one of the fathers of a family that was at the helm. One of the young gentlemen had brought a guitar to accompany the singing, which was neccessary on board. The young people gave forth niece pieces, not folk songs and that sort of thing, but pieces from operas as La muette de Portici or Fra Diavolo and the other latest things out.

The guitar was not considered as a serious musical instrument as can be seen from a statement of the Royal Musical Academy in 1838. The musical director at the Southern Scanian infantry regiment, Bengt Berckenmeijer (1807-1845), had in 1833 published a collection, “Tolf Sångstycken med accompagnement af Guitarre”, which he in 1838 sent to the academy for a judgement. The academy found that the collection

contained music of a kind that do not belong to the competence of the Academy to pass a judgement on… The songs are accompanied by an instrument, the guitar, which only may be useful in minor chamber music, for the most part being a pleasure for solitary persons, and the use and treatment of which neither belong to the professions of the Academy, nor is within its province of examination.

We can also be certain of that the Royal Musical Academy wouldn’t have approved of the “Componium Portatif, Contenant 1.680.536 Valses pour la Guitarre” which was advertised in 1832, but probably imported from France. To the same academy an innovation, guitar pegs with a star-wheel, by the cabinet-maker Johan Lillius was presented in 1835. As a matter of fact this innovation seems simply to have been the ordinary tuning mechanism found on most guitars today and which was introduced in the 1810s. Lillius’ pegs were mounted on a guitar made by a journeyman instrument maker named Lämmqvist. Neither would the academy have approved of the Tyrolean singers with guitar (Cittra) accompaniment who appeared in a concert in Uppsala in 1838.

The guitar is also found in the Gothenburg inventories from 1830 and onwards. Here are a list of guitars in inventories with their values in Riksdaler (Rixdollar):

– 1831 the wife of the cantor at the Gustavi cathedral And. Wickström “1 lutha med fodral 1.16” (1 lute with case)

– 1833 the widow Maria Tranberg “1 guitarre 3.16″ (1 guitar)

– 1834 the tailor and alderman Johan Bergström ” 1 guitarre utan str. -.16″ (1 guitar without strings)

– 1834 the merchant O. Chr. Medin “1 gammal guitarre -.32” (1 old guitar)

– 1834 the clerk of the Customs And. Wilh. Ekström “1 guitarre med låda 5.-” (1 guitar with case)

– 1834 the merchant Berndt Wahlgren “1 guitarre 13.16, div. guitarresträngar 1.-, 25 häften af solstycken för guitarre samt duetter och trior för guitarre, violin och flöjt, av åtskillige komposit 6.” (1 guitar, sundry guitarstrings, 25 parts with solo pieces for the guitar as well as duets and trios for guitar, violin and flute by several composers)

– 1834 the merchant Joh. Ad. Bolin “1 söndrig guitarre -.32” (1 damaged guitar)

– 1834 the merchant Olof Melin and his wife Maria Soph. “1 zittra 3.16” (1 cister)

– 1835 the stamp master Joh. Gust Winqvist “1 guitarre 6.32”

– 1836 the clerk Carl M. Buhrman “1 guitarre 10.-” (1 guitar)

– 1836 the wife of the baker And. Joh. Dahlgren “1 guitarre 3.-” (1 guitar)

– 1839 the wife of the book keeper Carl E. Jensen ” 1 guitarre med låda 10.-” (1 guitar with case)

– 1840 the brewer A, Wilh. Fernborg “1 guitarre 4.-” (1 guitar)

– 1841 the girl Charl. Thomasina Stangenete “1 guitarre 2.-” (1 guitar)

– 1841 the wife of the wholesale merchant David Carnegie “1 gitarr 2.-” (1 guitar)

– 1842 the shipmaster Jörg Johansson Möller born in Holstein “1 guitarre 3.16″ (1 guitar)

– 1842 the auditor at the Royal Goth Artillery E. J. Ståhle ” 1 cittra 1.16, 1 guitarr 6.32″ (1 cister, 1 guitar)

– 1843 the controller at the custom house Joh. Edberg “1 guitarre med 1 fodral 6.32” (1 guitar with case)

– 1844 the baker A. Holmström “1 gammal guitarr 2.32” (1 old guitar)

– 1844 the [musical?] instrument maker Joh. Heinrich Daug “1 gitarr 10.-, 1 gammal mandolin 1.-” (1 guitar, 1 old mandolin)

– 1845 the merchant Olof Germund Bronander “1 guitarr 2.-” (1 guitar)

– 1845 the clerk Thomas Sjögren ” 1 guitarr 10.-” (1 guitar)

– 1845 the wife of the public prosecutor J. C. Greiffe “1 guitarr 5.-” (1 guitar)

– 1846 the wife of the clerk Gust. E. Wigert “1 gitarr 3.-” (1 guitar)

– 1846 the merchant Jonas Elis Andersson “1 gitarr 5.16” (1 guitar)

– 1846 the book keeper Johan Frimen “1 gitarr med fodral 5.-” (1 guitar with case)

– 1846 the brewer Jonas Friman “1 gitarr 4.-” (1 guitar)

– 1847 miss Anna Maria Lindstedt “1 gitarr 5.-” (1 guitar)

– 1847 the wife of the wholesale merchant Charles Gust. Lindberg “1 gitarr 2.-” (1 guitar)

– 1847 mrs. Mathilda Carolina Witten “1 gitarr 12.-” (1 guitar)

– 1847 the wife of the farmer Olof Ericsson “1 gitarr med låda 2.32” (1 guitar with case)

– 1847 the widow of the farmer Joh. L. Osterman “1 zittra 1.-” (1 cister)

– 1847 the wholesale merchant Gudm. Niclas Åkermark “2 gitarrer 20.-” (2 guitars)

– 1848 the merchant Chr. Wilh. Daum “1 gitarr 5.-” (1 guitar)

– 1848 the dentist Aug. Ludwig Frenkel “1 gitarr med noter 3.-” (1 guitar with music sheets)

– 1849 the wife of the merchant’s clerk A. Wallerius “1 gitarr 3.-” (1 guitar)

– 1849 the dealer in fancy articles Ulrika Malmgren “1 gitarr med fodral 3.16” (1 guitar with case)

– 1849 the music teacher Carl Fredrik Sven Heinze “1 gitarr med låda 6.32” (1 guitar with case)

– 1849 the wife of the keeper of restaurant Peter Höga “1 gitarr 1.16” (1 guitar)

– 1849 the wife of the merchant Joh. Nic. Öhrn “1 gitarr 5.-” (1 guitar)

– 1850 the wife of the carriagebuilder Joh. Fromelius “1 gitarr 6.32” (1 guitar)

– 1850 the stockbroker Gust. Lund “1 gitarr 6.32” (1 guitar)

– 1851 the widow of the dean and vicar Vincent Brittberg “1 gitarr 2.-” (1 guitar)

– 1851 the tinner Carl Fr. Marténs “1 gitarr sämre 2.-” (1 guitar poor)

– 1851 the book keeper Carl Aug. Oscar Nordblom “1 gitarr 2.-” (1 guitar)

– 1852 the mechanician Carl Bernh. Matsen “1 gitarr -.32” (1 guitar)

– 1852 the captain Joh. Lorens Berg “1 gitarr 1.32” (1 guitar)

– 1852 the town musician Adolph Herrman “1 gitarr 3.-” (1 guitar)

– 1852 the wife of the merchant Joh. Andersson “1 gitarr 3.-” (1 guitar)

– 1852 the wife of the merchant Joh. Arnholt Wettergren “1 gitarr 5.-” (1 guitar)

– 1853 the wife of the merchant E. Svensson “1 gitarr med fodral 6.32” (1 guitar with case)

– 1853 the captain Hans Niklas Hagberg “2 gitarrer 4.-” (2 guitars)

– 1853 the merchant Hans Caspersson “1 gitarr och 1 notställ 3.16” (1 guitar and 1 musicstand)

– 1854 the wife of the chemist O. Th. Bergström “1 gitarr med fodral 1.-” (1 guitar with case)

– 1854 the town caretaker Joh. Ulrik Edman “1 cittra och en 1 violin utan strängar .16” (1 cister and 1 violin without strings)

– 1854 the wife of the merchant And. Backlund “1 gitarr 3.16” (1 guitar)

A Danish guitarist visiting Sweden in the 1830s was Frederik Carl Lemming (1782-1846). He seems to have stayed in Sweden during the period 1 July 1833 until 1 July 1835 and he was during this period employed at the Swedish Hofkapelle as viola player. During his stay in Stockholm he gave many concerts there at different places and there is a vivid description of him by a J.M. Rosén. He furthermore performed two concerts in Uppsala on 1 and 6 March 1831. From the city of Visby is in 1835 reported:

The Royal Chamber Musician Lemming arrived, announced by a short notice in the newspaper and he conquered the audience with violin and guitar in a fullvoiced vocal- and instrumental concert in the dining-room of the restaurant-keeper Unér…

Even if the Swedish publications for the guitar were far from the quality and musical interest that one may find on the continent we may not conclude that the Swedish guitarists only played a Swedish repertoire. Much music was imported and recently I acquired a collection of works for the guitar from a Swedish castle which may throw some light on what was played. The Swedish prints in this collection are in fact very few. Best represented are Giuliani with eight works, Carulli with four, Carcassi and de Call with two each. Other composers in the collection are de Bobrowicz, Bornhardt, Diabelli, Fürstenau, Hünten, Kapeller, Joseph and Conradin Kreutzer, Küffner, Legnani, Mertz, Molino, Neuland, Joachim Pettoletti, de Stoll and Johann Strauss Vater. The collection also shows the varied used of the guitar: as a solo-instrument, as an ensemble-instrument (duets, quartets) and as an instrument for accompaniment. Looking into guitar prints from other countries you sometimes find Swedish references. One examplet is Filippo Verini’s Spanish Guitar Petit Souvenir for the year 1836, printed in London but dedicated to Miss Carolina Hamilton. Carolina may be identical with Eva Gustava Carolina Hamilton (1818-1853) born at Husaby, Sweden, as daughter of Hugo David Hamilton (1789-1863). However, there is no proof of such a connection.

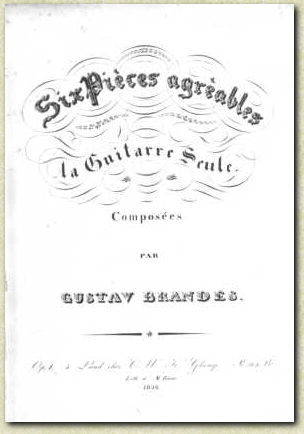

Another guitarist of some importance, Johan Jakob (Jean) Nagel (1807-1885), appeared on the musical scene in Sweden in the 1830s. He was born in Moravia and had been a pupil to Niccolo Paganini. Primarily he was a violin-player and as such employed in the “Hofkapelle” from 1830 to 1865. During the period 1830 to 1870 he published several collections of music for the guitar, including solo works, duos, guitar accompaniments to songs and he also composed a supplement to the seventh and eight Swedish editions of Carulli’s guitar method. From the beginning of 1852 he teached the Swedish Prince Gustaf on the guitar. Nagel’s works for guitar are not particularly interesting from a musical point of view and unfortunately the same can be said about almost all the guitar music printed in Sweden during this period. An exception is perhaps Gustav Brandes‘ (1798-?) only collection for the guitar, “Six pièces agréables…”, which was issued in Lund in 1836.

Title-page of ‘Six Pièces agréables’ by Gustav Brandes.

Sadly enough this was his first and only published opus but it contains some very niece pieces in a smaller format. Brandes was cello-player in the “Hofkapelle” between 1816-1818 and later became musical director at the Northern Scanian Infantry regiment. The earlier mentioned Anton Gustaf Dannström’s brother, Johan Isidor Dannström (1812-1897), was a celebrated singer and singing-master but also published some songs for the guitar during the 1830s and 1840s. Herman Wilhelm Neupert was music-teacher in Stockholm and composed a few solo pieces for the guitar between 1835 and 1838. In 1834 Per Erik Svedbom (1811-1857) printed his suggestion for a Swedish National Hymn, “Runesvärdet” with accompaniment for fortepiano or guitar. A manuscript by him, dated 1829, and containing guitar accompaniment to a poem by Esaias Tegnér is now in the Library of the Royal Musical Academy in Stockholm.

During the 1830s a promising young guitarist started his career. His name was Oscar Ahnfelt (1813-1882). In the newspaper Dagligt Allehanda the following advertisement was printed in 1841:

Song- and guitar-institute.

The guitar has in other civilized countries been so universally praised that it even in Paris has made a splendid entrance in the concert-hall. It has now, through the joint efforts by the musician Ahnfelt and the manufacturer Selling, improved considerably. One now would hope that the guitar, even in our country, would be successful notwithstanding the fact that several judges of art want to disclaim all its capacities as a solo-instrument. This, however, only prove that these judges have not made themselves familiar with the resources of the instrument. I therefore believe that I’m acceding to the wishes of many people when I’m uniting the Song-institute with one for guitar-playing. When teaching the guitar I intend to use a method, invented by me, through which many students at the same time can attend the lesson and accordingly pay a much lower fee. As soon as the students have learnt the fundamentals Mr Ahnfelt has kindly undertaken the charge of the guitar-tuition. The quarterly fee shall be paid at the start of the tuition and will amount to 13 rix-dollar 16 skilling for song and guitar, 8 rix-dollar for song only and 10 rix-dollar for guitar only, all in banco. There will be 6 lessons each week, namely 4 in song and 2 on the guitar. Those who wish to attend the lessons are asked to apply before January 6th when the first quarter starts.

Stockholm in December 1841.

C. J. Cronhamn

Nr 33 Regeringsgatan, on the second floor

Visiting hours every morning until 11 a.m.

The improved guitar which is mentioned above was in fact a 10-string instrument and there later was some argument whether it was Ahnfelt or the instrument maker Otto Fredrik Selling (1804-1884), who had “invented” this construction. Be that as it may, a 10-string guitar was hardly a novelty, as the decacorde already in 1826 had been introduced by Carulli and Lacote. The Ahnfelt-Selling instrument differs mainly from the decacorde in the construction of the head. Ahnfelt’s guitar is now preserved in the Music Museum in Stockholm. Ahnfelt had made himself known as an excellent guitarist, playing at concerts in both Stockholm and in the provinces. One performance by him in Stockholm in 1850 contained a nocturne and a “Fantasie Concertante” for guitar and piano over motifs from “La Somnambule” by Johann Kaspar Mertz as well as Giuliani’s “Grand duo concertante” for flute and guitar. During the 1840s Ahnfelt got more and more involved in the revivalist movement and became a travelling minister, singing sacred songs to his own guitar-accompaniment. This also meant that he later left his promising career as a solo guitar-player. Starting from 1850 he published a series of sacred songs to the accompaniment of the guitar or the piano which became immensely popular and has been printed in over 60 editions.

A relative to the above mentioned leader of the song- and guitar-institute probably was Johan Petter Cronhamn (1803-1875) who on his own statement had arranged 1000 songs for the guitar. Very little of this rather impressive work was ever printed. Occassional collections, mainly for song and guitar were published by Johan Fredrik Berwald, A. Colberg, Lars Gustaf Collin, Adolf Drakenberg, Erik Gustaf Geijer, Otto Lindblad, C. R. Norelius, Andreas Randel, George Stephens, Carl Erik Södling, Olof Wilhelm Uddén, Carl Johan Warell and Gunnar Wennerberg. Few of these published more than just one collection and in some cases we may even doubt that they played the guitar. All these publications show in any case that there was a market for guitar-music in Sweden during the first half of the 19th century. Altogether nearly 200 works for the guitar were published in Sweden from 1818 until the 1860s. In the Library of the Royal Musical Academy as well as in my own collection you may also find several manuscripts from this period, mostly songs with guitar accompaniment as is the case with the printed editions. As I have mentioned earlier much music for the guitar was imported and sold in Sweden.

Without doubt the most active period for the guitar in Sweden in the first half of the 19th century was the 1830s and 1840s. In 1840 a clerk in Uppsala offers “fundamental tuition in singing and guitar… Good and easy-to-play guitars at a reasonable price are for sale”. In the next year, 1841, “strings for guitar and violin, newly arrived” are advertised for sale by Jacobsson & Eckman in Uppsala. The same year a person wishes to borrow a guitar at a low rate and also get some tuition on the instrument. We can find a retrospective description in “Svensk musiktidning” from 1882:

Those of us who were active 40 to 50 years ago can remember how popular the guitar was then. In most families where music was practised a guitar usually was to be found and there hardly was any coffee-room or restaurant of a better quality that was not equipped with an instrument of that kind to entertain the guests. If some jolly young people had gathered at a merry party indoors, or if one had set out for picnics in the fair countryside on a beatiful summer’s day, the guitar often was brought. The demands on the performing amateurs were not so big as they generally are today and one was often satisfied with minor, simple and melodious song pieces. You lived in an age of romances and ballads, but there was poetry in the songs: the song-tradition of the south had moved up to the north! Many beatiful melodies, created by Crusell, Nordblom, Geijer, A. F. Lindblad and many other composers, Swedish as well as foreign, and arranged for guitar accompaniment by a Cronhamn, a Hildebrand etc., were carried by juvenile voices through the country! However, after having had the honour of this great popularity the guitar began to get out of fashion. Nowadays you will only find it here and there in the antique shops or as a nice sign in the windows of the musicshops.

In the late 19th century two Swedes are of particular interest as they both seem to have been in contact with Napoleon Coste and were great lovers of the guitar. They were the headmaster Adolf Hallberg in Sölvesborg and the businessman F. Schultz (or Schult) in Stockholm. Hallberg may possibly be identical with [Per?] Adolf Hallberg, born in Kristianstad 1846, student 1866, teacher in Sölvesborg and from 1912 in Gothenburg. F. Schultz was acquainted with the Danish guitarist Søffren Degen. One source says that Hallberg and Schultz were in contact with Napoleon Coste and acquired all his works. Coste’s unpublished ‘Duetto’ (WoO) was dedicated to ‘… Mr. A.F. Schult Souvenir d’amitié de Adolf Hallberg’. This manuscript is now in the Rischel-Birket-Smith collection in the Kongl, biblioteket, Copenhagen and it is possibly copied by Hallberg himself. Coste’s ‘Six Pièces originales’ op. 53 is dedicated to Hallberg. The Étude de genre no. 24 of Coste’s op. 38 and ‘Divagation Fantaisie’m op. 45 are also dedicated to Schultz. The guitar music collection of F. Schultz was later included in the Rischel-Birket-Smith collection. Finally I would like to mention two important collections of guitar music in Sweden even if their compilation belong to a later period. Still they contain much music from the first half of the 19th century. Both these collections are now housed in the Music Library of Sweden in Stockholm. The Carl Oscar Boije af Gennäs‘ (1849-1923) collection contains over 1000 items. In this you may find 126 works by Giuliani, 53 by Sor and not less than 37 autographs by Mertz. Aguado, Carcassi, Legnani, Matiegka and Zani di Ferranti are also well represented in the collection. Some of these works may well have been used in Sweden during the earlier part of the 19th century, but Boije af Gennäs certainly also acquired much abroad and in particular from Mertz’ widow. This collection is catalogued but this is unfortunately not the case with the other collection, compiled by Daniel Fryklund (1879-1965). The “Collection Fryklund” consists of not less than 900 instruments, music, books on music, programs, posters, pictures and c. 10000 autographs and letters. Among the instruments you find several guitars and some particularly fine lyre-guitars. There are several thousands of compositions for the guitar of which French music for song and guitar from the late 18th and early 19th century occupies a central place. Among the huge collection of autographs you can find some by Fernando Sor and Giulio Regondi.

References

I’m grateful to Eva Helenius-Öberg who provided me with information about Carl Eric Sundberg. I’m also grateful to Mats Krouthén who supplied me with information about guitarmaking in Gothenburg.

Bartolotti, Angiol Michele, Libro primo et secondo di chitarra spagnola. Facsimile edition. Geneva 1984.

Berg, Wilhelm, Bidrag till musikens historia i Göteborg 1754-1892. Första delen. Göteborg 1914.

Boivie, Hedvig, Några svenska lut- och fiolmakare under 1700-talet. Fataburen 1921 p. 51ff.

Bredvad-Jensen, Clas, Solistiskt gitarrspel i Sverige. Unpublished diss. The University of Lund 1972.

Collection Fryklund 1949. Hälsingborg 1949.

Coste, Napoleon, The Guitar Works of Napoleon Coste I-X. Editor: Simon Wynberg. Editions Chanterelle. Monaco. Cop. 1981 Davidsson, Åke, “Dulle Banérens” musiksamling, Svensk tidskrift för musikforskning 1953 p. 152ff.

Eliæson, Åke, & Norlind, Tobias, Tegnér i musiken. Lund 1946.

Fryklund, Daniel, Bidrag till gitarristiken, Svensk tidskrift för musikforskning 1931 p. 1ff.

Giertz, Martin, Den klassiska gitarren. Instrumentet, musiken, mästarna. Stockhom 1979.

Helenius-Öberg, Eva, Svenskt instrumentmakeri 1720-1800. En preliminär översikt. Svensk tidskrift för musikforskning 1977 p. 5ff.

Hellwig, Günther, Joachim Tielke. Ein Hamburger Lauten- und Violenmacher der Barockzeit. Frankfurt am Main 1980.

Karle, Gunhild, Kungl. Hovkapellet i Stockholm och dess musiker 1772-1818. Uppsala 2000

Jonsson, Leif, Offentlig musik i Uppsala 1747-1854. Från representativ till borgerlig konsert. Stockholm 1998.

Kjellberg, Erik, Kungliga musiker i Sverige under stormaktstiden. Studier kring deras organisation, verksamheter och status ca 1620 – ca 1720. Uppsala 1979.

Lundin, Claës, En gammal stockholmares minnen. 1. Stockholm 1904.

Lövgren, Oscar, Oscar Ahnfelt. Sångare och folkväckare i brytningstid. Stockholm 1966.

Montgomery-Silfverstolpe, Malla, Memoarer. Andra delen. 1804-1819. Stockholm 1914.

Møldrup, Erling, Guitaren – Et eksotisk instrument i den danske musik. København 1997.

Nerman, Ture, Otto Lindblad – ett sångaröde. Uppsala 1930.

Norlind, Tobias, & Trobäck, Emil, Kungl. hovkapellets historia 1526-1926. Stockholm 1926.

Nyberg, C.F. Bericht über die Gitarristik in Schweden. Der neue Pflug, 3. Jahrgang, heft 6., juni 1928 p. 69ff.

Ozolins, Berit, Musiknotiser i bouppteckningar åren 1690-1854. Arkivstudier inför en undersökning om Göteborgs musikhistoria. Unpubl. diss. University of Gothenburg 1970.

Pettersson, Monica, De dansanta grevebarnen på Skokloster. Tidig Musik 2003 No. 3 p. 7.

Powrozniak, Josef, Die Gitarre in Russland, Gitarre + Laute 1979, Nr 6, p. 18ff.

Redway, Virginia Larkin, Music directory of early New York city; a file of musicians, music publishers and musical instrument-makers listed in New York directories from 1786 through 1835, together with the most important New York music publishers from 1836 through 1875, by Virginia Larkin Redway New York, The New York public library, 1941

Rudén, Jan Olof, Music in Tablature. A Thematic Index with Source Descriptions of Music in Tablature Notation in Sweden. Stockholm 1981.

Sparr, Kenneth, Die Gitarre in Schweden bis zur Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts Gitarre & Laute (14/ 1992 Heft 2) pp. 57-64

Sparr, Kenneth, En samling äldre gitarrmusik från Skottorps slott. Gitarr och luta (1989, nr 1) p. 9ff.

Sparr. Kenneth, Gitarren i Sverige till 1800-talets mitt Gitarr och Luta (24/1991 nr 1) pp. 3-11

Sparr, Kenneth, I concertsalar skulle guitarren aldrig våga sig… Gitarr och Luta (26/1993 nr 3) pp. 23-24

Sparr, Kenneth, La chitarra in Svezia fino alla metà del XIX secolo. il Fronimo nr 78 1992) pp. 8-17

Sparr, Kenneth, La suédoise – Music in Baroque Sweden. Introduction & Commentary. Musica Rediviva MRCD 003.

Sparr, Kenneth, Om svenska gitarrskolor och instrumentmakare. Gitarren i Sverige under tidigt 1800-tal. Gitarr och luta (21/1988, nr 3) p. 46ff.

Sparr, Kenneth, The Guitar in Sweden to the Mid 19th Century. Soundboard (1990, vol. 17, nr 1) p. 16ff

Sparr, Kenneth, Musik för gitarr utgiven i Sverige 1800-1860. Svenskt musikhistoriskt arkiv Bulletin 24. Stockholm 1989 s. 20ff. Också publicerad på engelska som Music for the Guitar Printed in Sweden 1800-1869

Sundström, Einar, Notiser om drottning Kristinas italienska musiker, Svensk tidskrift för musikforskning 1961 p. 302ff.

Svenskt biografiskt lexikon, Vol. 15, p. 752

Torpp Larsson & Danner, Peter, Catalogue of the Rischel and Birket-Smith Collection of Guitar Music in The Royal Library of Copenhagen. Columbus, 1989.

Verino, Filippo, Tre pezzi (da “Petit souvenir for the year 1836”) per chitarra revisione e diteggiatura di Fabio Rossini. Ancona, 2005.

Vi äro musikanter alltifrån Skaraborg – studier i västgötsk musikhistoria. Skara 1983. Vretblad, Patrik, Konsertlivet i Stockholm under 1700-talet. Stockholm 1918.

Wells, Elizabeth & Nobbs, Christopher, European Stringed Instruments. Royal College of Music Museum of Instruments. Catalogue. Part III. London 2007 p. 127

Additions and corrections are most welcome to kenneth.sparr@bredband.net

© Kenneth Sparr

http://www.tabulatura.com/SWEGUIT.htm